“Fascism” is a challenging word for a challenging moment, and its origins may bear lessons for us.

This word should make you uncomfortable. It should challenge you—and all of us—especially today, Election Day, when we exercise its antithesis.

You might find my choice alarmist. You might find my ensuing explication not alarmed enough. You may not want to think about it. You may think I’m biased—or worse.

But I believe the word meets the gravity—if not reality—of the moment in 2025.

Fascism.

It’s my choice for Word of the Year, which I am transposing here, a blog on word origins, as my “Etymology of the Year.”

Fast Mash

Today’s post is lengthy, so here’s a handy overview:

- In addition to its prominence in events and discussion in the US and abroad, search interest for fascism is notably high in 2025

- Fascism, first recorded in 1921, is from the Italian fascismo, based on fascio, a political “group”

- Benito Mussolini organized nationalist, anti-socialist groups into his National Fascist Party in 1922 and ruled until 1943

- The Italian fascio also means “bundle,” as did its Latin root, fascis

- The Latin plural, fasces, referred to a bundle of rods around an axe carried by lictors before magistrates, a custom with Etruscan origins

- The fasces were a symbol of supreme power in Ancient Rome, later used as a symbol of unity in the early American republic

- Antifascist is also first recorded in 1921; its German counterpart was shortened to what English borrowed as antifa

A word on the Word of the Year

I should know a thing or two about the Word of the Year enterprise; I oversaw it for Dictionary.com for several years.

The Word of the Year has power. An effective choice not only captures the zeitgeist of the past year in life and language, but it also resonates with people’s lived experiences and gives expression to their prevailing concerns.

Even in this age of AI, we still look up words in dictionaries because we still—and still should—hold them as arbiters and authorities on this fast-changing thing we call language.

But it’s been my experience that, for as much as major dictionaries try to make their selection based on data, people look to the Word of the Year for an emotional summary, not objective statement, of how the past 365 days felt—in a word.

We orient ourselves around that word and judge the choice by whether or not it rings true or misses the mark—which can happen when dictionaries strive to avoid the faintest whiff of politics.

But we are not in normal times. We can’t afford to avoid politics out of politeness.

The evidence of data—and our eyes

While it’s a big world restless with activity, there’s no doubt President Donald Trump excels at controlling the narrative and making everything else a sideshow—to great consequence. In the US, we are seeing use of military force against citizens and migrants. We are witnessing rising nationalism, racism, and xenophobia. State capitalism. Censorship. Corruption. Economic isolation and military expansionism. Unlawful executive action and overreach. Persecution of political opponents. A whim-driven strongman.

These are hallmarks of, well, fascism. Trust me. I looked up the word in the dictionary. I used to help run the dictionary.

But this isn’t just how I feel. There’s data to back it up, and not just its proliferation in left-wing media or countervailing objection to use of the term on the right. And there has been data, as the term has had non-seasonal elevated interest since 2015.

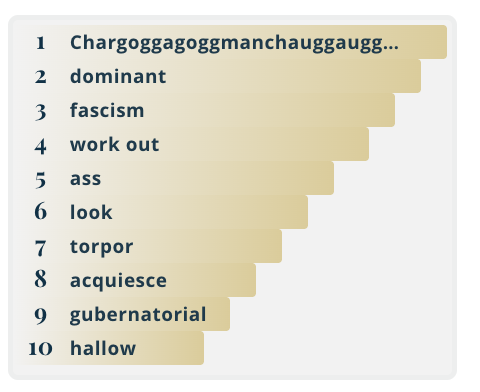

Fascism has consistently been in the top-ten trending searches on Merriam-Webster. My spot check while writing this sentence finds it at #3 in their trending module.

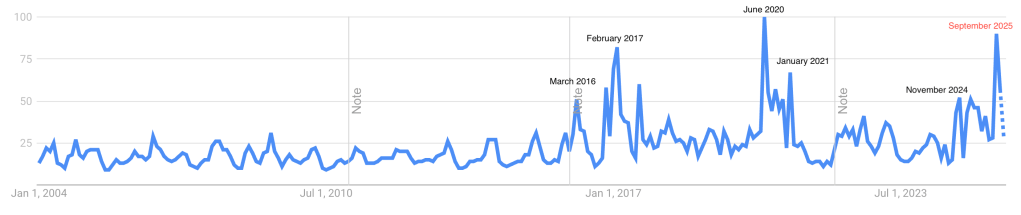

Google search data shows significant spikes in lookups for fascism since November 2024, climbing in September 2025 to just short of historical highs during Covid and George Floyd protests in June 2020 during Trump’s first presidency.

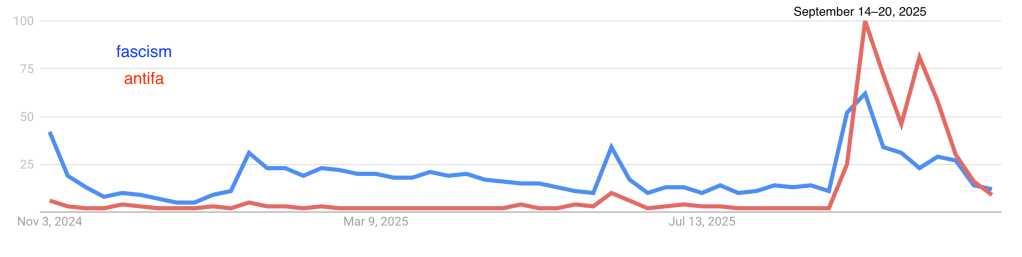

This September, Trump issued an executive order designating antifa (sometimes capitalized as Antifa) as a domestic terrorist organization that some on the right wing blamed for Charlie Kirk’s abhorrent assassination. Antifa—ultimately short for antifascism, as we will see—is, in fact, a decentralized left-wing movement that does not universally espouse political violence. Lookups for antifa overtook fascism at this time, though paling in comparison to their surge in June 2020.

Why people look up the words they do I can’t say for certain. Sometimes it’s for actual information. Other times it offers a deeper assurance or understanding in the midst of tribulation. But there’s no doubt fascism, whether you fear it’s here or think I’m freaking out, is on our minds and in our discourse like never before in 2025.

So, if you’re still with me, let’s now turn to the ancient etymology of this very 2025 word.

Never miss a mash! Feed your inner word nerd and subscribe to get Mashed Radish fresh in your inbox.

The etymology of fascism

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) first records Fascism (with a capital) in 1921 in specific reference to the “nationalist political movement that controlled the government of Italy from 1922 to 1943 under the leadership of Benito Mussolini.”

The dictionary cites a haunting passage from New York’s Syracuse Herald. Its misreading of the historical moment makes the word fascism all the more urgent today: “No doubt fascism is a transitory phenomenon.”

As the model of Italian fascism spread in Europe after World War II, so too the term spread as the name for similar ultranationalist right-wing ideologies— including Nazism—that opposed communism, socialism, and liberalism and promoted ethnocentric racial superiority under a charismatic dictator.

I paraphrase the OED for this generalized sense of fascism, which it cites in 1923 in London’s Contemporary Review, a scholarly Christian magazine, in another passage that underestimated the events of the day: “Fascism in Germany will never be more than one of several factors.”

There are lessons for us in history. There are lessons for us in dictionaries.

English took fascism from the Italian fascismo, which combines fascio and -ismo, the Italian equivalent to –ism.

In Italian, a fascio (pronounced like fash–sho) can refer to a “sheaf” of grain or paper or a “bundle” of clothes, among other specialized senses—including, historically, an association of regional or local political and social groups organized around a common cause and revolutionary action. Here, I paraphrase the Grande dizionario della lingua italiana, an Italian counterpart to the OED.

In the late 1800s, many of these groups—or fasci, to use the plural of the Italian fascio—were actually socialist workers’ leagues. But the term became associated with anti-socialist ones in the late 1910s revved up and rallied together by Mussolini, who united his fasci di combattimento, or “fighting bands,” under the National Fascist Party in 1921 as he rose to Il Duce, or “The Leader.”

The National Fascist Party, or Partito Nazionale Fascista, was nationalist, authoritarian, corporatist, expansionist, conservative, and antisemitic, believing modern Italy was the scion of Ancient Rome. So much so the party even adopted as its emblem the Ancient Roman insignia of power, the Latin word for which is the ultimate source of the party’s name: fasces.

The fasces: symbol of Roman power

The Latin fasces (pronounced like fahs-kays) is the plural of fascis, which, like its Italian derivative fascio, had a number of senses signifying sundry materials, especially agricultural quantities, wrapped together: “bundle, pack, parcel, load, burden, baggage.”

In the plural, fasces named the bundle of rods and ax carried before magistrates by lictors as symbols of their authority and power—or imperium in Latin. Measuring nearly 5 feet long, the fasces bound elm or birch rods together with a red leather cord around a single-headed ax, which projected from the bundle.

Hence the name.

Magistrates were various high-ranking officials in Ancient Rome, the most prominent of which were consuls or dictators during the republic—and kings before them, emperors after.

The more powerful the magistrate, the greater the number of fasces borne as a visual—and intimidating—expression of their power. Dictators had 24 lictors bearing fasces, for instance. Consuls 12, praetors 6. Certain priests were granted fasces, and they bore 1.

Lictors (Latin, lictores) were the magistrates’ attendants, accompanying them wherever they went. Lined in a single file, they carried the long fasces on their left shoulders. But the fasces weren’t just symbolic. They were functional. Lictors were deputized to implement magistrates’ various rights—including, in many contexts, to administer corporal and capital punishment.

Hence the rods. Hence the axe.

Except within the city of Rome, where the axe was generally removed from the fasces to represent the special right of its citizens to appeal magisterial judgment ahead of any summary execution.

For, Roman imperium, or supreme power, involved military command as well the authority to interpret and execute the law.

With fascio, Italian applied the Latin fascis, “bundle,” as a figurative name for a “group” or “association”—a bundle, a tight-knit band of people.

It’s this sense of fascio that serves as the immediate source of fascismo, and it’s this sense of fascio, of “group,” that is additionally instructive now.

I agree with philosopher Michael Fuerstein that it’s groupishness—our dogged, defensive, divisive tribalism, exacerbated by social media, digital fragmentation, and demographic segregation—that threatens so much of our democracy today. Most of us don’t wake up each day and go, “Where can I usher in some more fascism today?” But we are dug in, and a vocal and powerful few are rolling over the rest of us.

At the same time, Mussolini’s fascism certainly—and pointedly—evokes the Roman fasces, not only as word and symbol, but also in its totalitarian conception of power, of rulers who are both judge and executioner.

The fasces: symbol of American democracy?

Others adopted the fasces, too—including the United States, where they feature extensively in official iconography of this democratic experiment.

Two fasces flank the US flag behind the Speaker’s rostrum in the US House of Representatives. Two fasces cross on the bottom of the seal of the United States Senate. Fasces—without axe—adorn a doorway in the Oval Office, and Lincoln rests his arms on a seat of state decorated with similarly axe-less rods. The reverse of the Mercury Dime, minted from 1916–1945, bore an engraving of the fasces.

The US drew upon this Roman imagery long before Mussolini’s fascism, however, not only because the Founding Fathers heavily tapped Roman republicanism, but also because the fasces evolved new meanings as a symbol after Rome—particularly of strength in unity, a bundle of sticks being harder to break when bound together than on their own, much as the American colonies, the United States, were mightier when allied in their revolt against British rule.

I don’t have to go far to behold fasces. The namesake of my city, Cincinnati, is Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, a Roman statesman who served as dictator—which, in the Roman republic, was a king-like supreme magistrate appointed during emergencies. After squashing a warring Italic tribe, Cincinnatus, as the legend goes, relinquished his fasces to assume the farmer’s plough.

And that is how Cincinnatus is so figured, handing over the fasces while leaning on his plough, in a notable statue in the riverfront park outside my apartment. Held up as a model of civic virtue—though Cincinnatus himself opposed plebeian rights—Cincinnatus lent the genitive form of his multisyllabic name to the Society of Cincinnati, founded in 1783 in the US by Henry Knox for officers who served in the Continental Army and their male heirs. George Washington, himself often depicted with various fasces, was elected as the society’s first president.

Unbundling the roots of fasces

An artifact from the 600s BCE discovered in an Etruscan tomb in an historic city north of Rome strongly indicates the fasces have Etruscan origins.

And while the Romans ultimately conquered their neighboring Etruscans, they also borrowed significantly from its culture and language. (Such multiculturalism, even if by subjugation, always strikes me at ironic odds with that fascistic frenzy for a purity of nationalist identity.)

As for fasces itself, it does not seem to have Etruscan roots. While far from certain, evidence suggests the Proto-Indo-European *bhakso-, “band” or “bundle,” with some Celtic cognates and possibly even the English bast, fibrous plant material used to craft rope and other such goods.

Fascis yields other words in English, including fascicle (separately published sections of a book, as the OED once was) and fascine (bundle of wood or the like used to strengthen embankments or ease marshy paths).

Closely related to fascis is fascia, Latin for “bandage,” borrowed directly into English for architectural and anatomical meanings. Ever suffer from plantar fasciitis? (I do. Ouch.) That’s inflammation of the fascia—broadly, a sheath of tissue that holds muscle together—in the sole of the foot.

Apparently, fascia has also referred to a business’s nameplate, and in British English, a dashboard in a car and even a mobile phone covering.

More deliciously, in Spanish, fascia became fajita, “little strip,” as of beef or chicken served with tortillas, vegetables, and other fixings.

More obscurely, in French, fascia became fess, a heraldry term for a broad horizontal stripe on the middle of a shield.

More offensively, speaking of French, some suggest fascis may have ultimately produced the French fagot, a bundle of sticks used for fuel—and later developing into an extremely anti-gay slur. The history of this latter term, however, is uncertain, complicated, and much debated.

More improbably, the American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots holds open the possibility that fascis is connected to fascinate.

Fascinate comes from the Latin fascinum, a widely witchy word for “evil eye, jinx, witchcraft, spell, charm, amulet.” It was also slang for “penis.” In Ancient Rome, a fascinum was indeed an amulet in the shape of a phallus—a bundle of sorts—believed to ward off envy through its magical virile powers.

Fascinating. Or at least that’s one way of putting it.

Lessons from antifascism

The lessons we can learn from dictionaries on fascism aren’t just haunting. They are also hopeful.

The same years, 1921 and 1923, we saw the Oxford English Dictionary’s earliest attestations of fascism in English are also the same years we see first-known records for its opposite.

The OED enters anti-fascist as an adjective for “opposing fascism” in 1921 in a reference in the New York Herald to the efforts of Francesco Saverio Nitti, Italian scholar and statesman who served as his country’s prime minister as the head of the Italian Radical Party.

In 1923, the OED cites anti-fascist as a noun for “German anti-fascists” in the Irish Times. Anti-fascism it records that same year.

The German equivalents, Antifaschimus and antifaschistich, are found right around this time, 1924–1925, and it’s from their shortening that we get Antifa as early as 1931. English borrowed it—and lowercased its initial A over time—come 1946.

Antifa first referred to opposition to German fascism during and following World War II, later expanding to signify “a political protest movement comprising autonomous groups affiliated by militant opposition to fascism and other extreme right-wing ideologies.”

That same year, 1946, the OED cites a passage of World Today that asks a question as pressing for us today as then: “It is a matter of speculation whether the course of German politics would have been different if ‘Antifa’ had been encouraged.”

I say, let’s not make it a matter of speculation in our current moment. Without violence. United under a renewed commitment to democratic values.

In 2026, now, let’s make the word antifascism as prominent as fascism.

The Etymology of the Year has been a sporadic exercise at Mashed Radish, with winners picked in 2016 and 2017. I felt 2025 deserved an announcement, too.

Leave a comment