In etymological memoriam of a dog of such great heart—and soul.

My father-in-law, Bob, wasn’t exactly a dog person.

I don’t think he had pets growing up in Kansas and Montana in the 1930–40s, as his family had to move around for his father’s work.

But he loved Hugo.

One Christmas, when my wife Olivia and I had driven up to Cincinnati from Austin, Bob was sitting at his kitchen table when Hugo placed his forepaws on his knees.

Hugo peered his brown eyes up through his shaggy brows. Bob gazed down and said, in a direct address that harmonized gravity and levity, “Hugo, you have such soulful eyes.”

Bob reserved his words, especially later in life, but when he did speak, he was given to pithy pronouncements.

Hugo, for his part, wasn’t a dog’s dog. He loved people. He loved Bob. And he was given to long, pleading looks from those soulful eyes.

Soulful is no incidental word for a dog named Hugo, whom we put down peacefully at home last month after nearly 14 happy, hearty years.

The clinician—such a cold, sterile title for the warmest, most compassionate woman—had asked me if there was any significance to the name Hugo.

Of course I had an answer.

Hugo’s origin story

My ex-wife Amanda and I rescued Hugo in Minneapolis late in 2012.

I was skeptical of getting a dog at this point. We were on the go, frequently traveling and with plans to move all while I was still finishing my master’s back in Cincinnati.

Eventually I was persuaded—at least in the abstract—and we applied to adopt a smaller, hypoallergenic dog whose leading breed was listed as Miniature Schnauzer.

Amanda suggested we come up with a name fitting for a dog with Germanic heritage. I hadn’t started Mashed Radish at this point, but I set myself to the onomastic task.

Traube. That’s what I first came up with.

From the German for “grape.” Die Traube. Amanda and I had bonded enough over a fondness for pinot noir that I apparently deemed it worthy of dubbing a pup.

Our would-be Traube went to a different home—I recall there being a competitive adoption environment at the time—and my doubts reared their head again.

But one cold night in Minneapolis, when 4:00pm already seemed as dark as 4:00am, we were at the Midwest Animal Rescue Shelter.

The staff led us around a corner to a stall where a pair of brown eyes peered up through shaggy brows. It was love at first sight.

It was Hugo.

Well, technically, it was Smokey. That was his original name, not inapt for his grayish white coat, before he was given up at about a year, year and half.

I’ll never understand how anyone abandons a dog, let alone this dog of all dogs. The shelter employee intimated the previous owners wanted a bigger one.

There was no question, no doubt, that Smokey was coming home with us.

Amanda took on the paperwork. I took Smokey out for our first walk—the first of our many thousands of miles, from the snows of Minneapolis to the sands of Laguna Beach to the greens of Ireland to the oaks of Austin and finally along the river of Cincinnati.

Smokey took a dump. And he took to the name Hugo immediately.

The “heart” of Hugo and Germanic dithematic names

Hugo ultimately comes from a Germanic base meaning “heart, mind, spirit.”

I’m sure I devised a list of alternative appellations for Hugo, but I don’t remember any of them. When you have the name, you have the name.

I do remember jotting out some primitive etymological notes on Hugo in the den at the back of the Minneapolis house we rented—the same room where a few months later I would concoct Mashed Radish in all its early, bright pink glory.

The root of Hugo is reconstructed as the Proto-Germanic *hugiz, meaning “thought, understanding, mind.” In the ancient world, it was widely believed that the heart—not the brain—was the seat not only of emotions but also of cognition and the soul. So, it’s little surprise that, as the Proto-Germanic *hugiz evolved in its descendant tongues, it added to its original intellectual senses “heart” and “soul.”

Over time, the root was commonly incorporated into Germanic given names, such as Hubert. Hubert literally means “bright-minded” or “bright-hearted.” It combines the Old High German hugu, a scion of the Proto-Germanic *hugiz, and berht, meaning and related to English’s own “bright.”

(Old High German was an early West Germanic language spoken up to around the 1200s in areas that are now part of southern Germany, Austria, and Switzerland and from which modern German arises.)

As a compound name, Hubert isn’t special—and I don’t mean because the name is no longer in vogue. Compound names like Hubert were widespread in Germanic history, particularly for male given names. Such names are technically called dithematic, meaning they are composed of two stems.

Many survive today and remain popular, such as:

- Edward. Literally, “prosperity guard.” Old English ead (prosperity) + weard (guard).

- Henry. “Home ruler.” Old High German heim (home) + rihhi (ruler).

- Robert. “Fame-bright.” Old High German hrod (fame) + berht (bright).

- Richard. “Strong in rule.” Form of Old High German rihhi (ruler) + hard (strong, hardy).

- William. “Will helmet.” Old High German will (will, desire) + helm (helmet, protection).

Picking up on any themes in Germanic dithematic names?

These names, and themes, weren’t the exclusive domain of men:

Gertrude is “strong spear,” blending Germanic roots for “spear” (gar, ger) and “strength” (þruþ). That old þ letter is called thorn, corresponding to the th in thick.

The second part of Mildred—“gentle in strength”—features a form of that same þruþ, the first being “mild,” originally conveying a merciful kindness.

Audrey also contains “strength” and is ultimately short for Etheldred (“noble might”), not to be confused with Aethelred (“noble counsel”), whose second component is related to the verb read and found in Alfred—literally, and delightfully, “elf-counsel.”

The Ethel-/Aethel- piece, from Germanic roots meaning “noble” and often referring to such ancestry, also appears in Adelaide, from the same source as Alice (“noble character.”)

The “noble” root also appears in Albert (“bright-noble”), whose -bert—lest I never escape this rabbit hole—leads us back to Hubert.

(Once you get started with these Germanic name elements, you can’t stop. If you want to wander the rabbit warren more, browse Behind the Name.)

A more recognizable name, at least to my ear, featuring the Germanic hug- is Howard, “heart-brave,” and whose –ard is shared by Richard.

Howard is the French version of Hughard, which sounds like 1) asking someone to really bring it in and 2) the opposite of Hugbald, whose –bald actually means “bold.”

Other names that have embraced hug- sound like they—nay, do in fact—come from bear-skinned ballads, such as Hygelac. Hygelac, “courageous battle, offering,” was a king of the Geats, a northern Germanic tribe, and is mentioned in Beowulf, itself “bee-wolf,” a kenning for “bear.”

Now, names get nicknames. And common names get common nicknames.

Teds are Edwards. Dicks are Richards. Bobs are Roberts. And Huberts, Hughards, Hugbalds, and Hygelacs?

They are Hughs, effectively.

Never miss a mash! Feed your inner word nerd and subscribe to get Mashed Radish fresh in your inbox.

A brief history of Hugh and some of its famous bearers

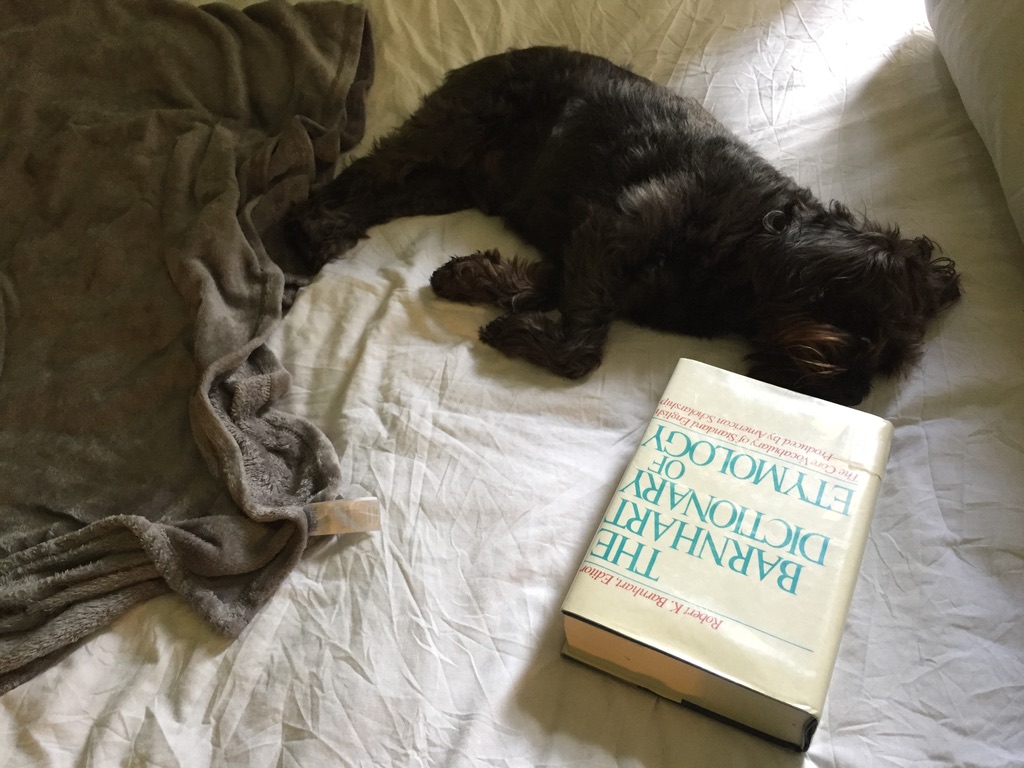

Back in my Minneapolitan den, I didn’t yet have a copy of Patrick Hanks and Flavia Hodges’s A Dictionary of First Names from Oxford University Press.

But for this post, it was the first text I consulted as I scrawled my jottings in a composition notebook—which habit I did already form back then.

The entry for Hugh in A Dictionary of First Names begins:

English: of Germanic origin, brought to Britain by the Normans. It is derived from the element hug heart, mind, spirit. Originally, the name was a short form of various compound names containing this element.

Here’s more from Hanks and Hodges:

- In Scotland and Ireland, Hugh has been used as an Anglicized form of the Gaelic names Aodh, Ùisdean, and sometimes Eóghan

- Cognates include the French Hugues, the Italian Ugo, and Welsh Huw

- Hugo is a Latinized variant also used in Dutch and German

Hugo.

As in Hugo Ferdinand Boss—the German businessman who started the fashion brand Hugo Boss in 1924.

When strangers, rightfully adoring my dog Hugo, would ask his name, they would frequently offer up Hugo Boss.

Not-so-fun fact: Hugo Ferdinand Boss was a Nazi.

(My dog Hugo was very much not.)

To Dutch and German we should add Portuguese and Spanish, as in Hugo Chavez—another notorious Hugo strangers would offer up after learning Hugo’s name.

According to Social Security data available since 1900, the name Hugo peaked in popularity in 1901 as the 328th top male given name, followed by 1911 (355) and 1914 (363). Fast forward to 2002–2004 and Hugo claimed spots in the 360s. It was 403 in 2024.

Early instances of Hugo are recorded as early as the 700s. The name became popular in the Middle Ages due to association with nobility, including Hugh the Great.

Living from around 898–956, Hugh the Great was a powerful Duke of the Franks and Count of Paris. Son of Robert I of France, Hugh begat Hugh Capet, who started the Capetian dynasty, which ruled France for almost 1000 years. The Franks were a Germanic people whose name lives on in frank, France, and other place names like Frankfurt.

Fun fact: in the complicated and nerve-wracking process of getting him to Ireland, Hugo first flew from LA to Frankfurt, Germany, where the EU processes inbound animals. I have not been to Frankfurt; Hugo had.

Going back to French, Besançon Hugues was a Genevan political and religious figure in the late 1400s and early 1500s whose name—and profile—apparently helped shape the Swiss German Eidgenoss (“oath associate”) into Huguenot. While Hugues had some Protestant sympathies, he remained a Catholic. John Calvin’s birthplace, Geneva, was closely connected to Calvinism, which the French Protestant Huguenots largely followed.

Earlier in the 1100s, Sir Hugh de Paduinan was also a political and religious figure, a Scottish Norman Knight Templar given land in southwest Scotland. He lent his name to a village there, Hugh’s town—which became Houston and went on to christen Clan Houston, from which Sam Houston, namesake of the Texas city, is descended.

Some two and half hours northwest of Houston is Austin, where I once helped Olivia read Chaucer’s “The Prioress’s Tale” for an English class themed on “charity” she TA’d. Let’s bring back in Hanks and Hodges:

Little Hugh of Lincoln was a child supposed in the Middle Ages to have been murdered by Jews in about 1255, a legend responsible for several outbursts of anti-Semitism at various times. The story is referred to by Chaucer in “The Prioress’s Tale.” He is not to be confused with St. Hugh of Lincoln (1140–1200), bishop of Lincoln (1186–1200), who was noted for his charity and good works, his piety, and his defence of the Church against the State.

St. Hugh of Lincoln is depicted with a swan, alluding to a tale about a swan in the village of Stow, Lincolnshire, who befriended and guarded Hugh, a lover of animals, like a dog.

Fast forward to the early 1800s when one Thomas Hughes, an English shoemaker, willed a high school be built on his property atop a hill in Cincinnati. One indeed was in 1853, honoring him as Hughes High School—where I did some student teaching for that very master’s degree whose finishing had me driving back and forth from the Queen City to the Twin Cities, a young Hugo sometimes my passenger.

The root of Hugo, via its English and French short forms, survives in other surnames: Hewitt, Howe, Huddleson, Hudson, Hutchins, and Pugh.

Hudd, apparently, was a hypocorism—or pet name—of Hugh.

Pet pet names

Our pet Hugo had many a pet name, including Deeps.

How do you get Deeps from Hugo?

Well, it started with a bit of rhyming reduplication in the form of Hugo Balugo, to which I would sometimes insert Roberto.

(The connections to Bob are uncanny. Roberto is an Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish form of Robert, like Hugo, a Germanic dithematic name, commonly clipped to Bob.)

Hugo Balugo inspired Loogsies Boo, then Loogsies and Loogs, by various processes of aphesis and diminution and, of course, baby talk. From there I fashioned, for idiosyncratic reasons I’ll spare you here, Deep Loogs, which prompted the alliterative Deepsy Doodles and, finally, simply, Deeps.

Olivia favored Little One.

Hugo was my dude. One of my other, human dudes—who will be chucking, again for reasons that warrant no elaboration here, at Stow—occasionally called him Huge Bro—whose fatuous provenance likewise deserves no explication.

Which brings us to huge.

And more importantly, hug.

Hug, hygge, and other dogged cognates of Hugo

The word huge is not related to Hugo. Evidenced in English by the 1200s, huge is shortened from the French ahuge, whose further origin is unknown.

But the word hug might be, though our Hugo preferred giving kisses— and receiving all sorts of rubs and scratches—more than he cared for being held.

Hug is first recorded in English surprisingly late to me: the 1560s. The origin is obscure, but it could indeed be linked to the very same Germanic roots of Hugo.

One proposal is that hug is from or at least influenced by the Old Norse hugga, “to comfort,” from hugr, the Nordic offspring of the Proto-Germanic *hugiz, “thought, mind” and later “heart.”

The Old Norse hugga eventually evolved into the Danish hygge, naming that “quality of coziness and comfortable conviviality,” as the Oxford English Dictionary précises it—and that Olivia and I have felt in shorter supply absent Hugo.

I worked remotely for most of Hugo’s life, so he and I were always together, including for all these Mashed Radish posts over the years—until Olivia entered his life about seven years ago, when he never left her side.

Except when his vital functions needed attention: food, bathroom, chase/ball, fear from thunderstorms or fireworks, and apples.

His morning, afternoon, and evening walks, Irish rain or Minneapolis snow or California and Texas shine, measured my day. Breakfast and dinner measured his, even during time changes, which somehow never manage to confuse a canine’s internal clock. He’d be underfoot in the kitchen during meal prep, though human food was only the most occasional of treats. Except those apples. Most nights after dinner in the latter years of his life, I have enjoyed an apple. Even when he became mostly deaf, Hugo still recognized the rattle—or postprandial routine—of the crisper drawer. He’d spin and spin and then dog my field of vision as I’d dole out bits of Fuji flesh.

What about English? What’s the lineage of *hugiz in this Germanic language? It developed into the Old English hyge, pronounced like “who-yay.”

The Old English hyge also meant “mind, heart, soul,” with secondary senses of “courage” and “pride” as well as “purpose” and “determination.”

Just as the Germanic *hugiz combined with other elements to form many a name, so hyge helped build many words in Old English—including, as we saw, the name Hygelac, whose lac variously meant “sport, game, battle, gift, offering, sacrifice.”

I can’t resist sharing examples from Henry Sweet’s The Student’s Dictionary of Anglo-Saxon. It gives me comfort knowing a close cognate to Hugo once headed so many words in English. Flip to page 97 if you’re referencing your copy at home.

- hygebęnd, mind-bond, natural tie

- hygeblind, infatuated

- hygeblīþe, glad

- hygeclǣne, pure-minded

- hygecræfte, faculty, wisdom

- hygecræftig, wise

- hygefæst, wise

- hygefrōfor, consolation

- hygegǣlsa, sluggish

- hygegāl, wanton

- hygegār, wile, device

- hygegēomor, sad

- hygeglēaw, prudent, sagacious

- hygegrimm, fierce, cruel

- hygelēas, thoughtless, foolish, reckless

- hygelēast, levity, folly, recklessness

- hygemǣþ, reverently

- hygemēþe, mind-wearying

- hygerōf, brave

- hygerūn, secret

- hygesceaft, mind, heart

- hygesnottor, wise

- hygesorg, sorrow, anxiety

- hygetēona, injury, wrong, insult

- hygetrēow, faith

- hygeþanc, thought

- hygeþancol, thoughtful

- hygeþrymm, pride, courage

- hygeþrȳþ, pride

- hygeþyhtig, brave

- hygewięlm agitation of mind, anger

- hygewlanc, proud

Hyge morphed into the Middle English high, which faded out early in this phase of our tongue. Its related verb was hygcan, “to think, hope.”

With the same -th suffix in birth and death, height and depth, and strength and growth, hycgan produced hight, a now-obsolete noun (with equivalent verb) variously meaning “hope, happy expectation, joy, delight, trust.”

Via the Old English hogu and its verb hogian, English once had how, a noun hanging in the hyge pack (and hanging on the language into the late 1800s) that expressed many of hight’s emotional antonyms: “care, anxiety, trouble, sorrow,” articulable in the verb how, too.

And how. How how and hyge express the full gamut of emotions, including of having—and losing—a dog, especially one as sweet as Hugo.

Finally still, still soulful

Of course I had an answer for the clinician when she asked how Hugo got his name.

And of course, I didn’t deliver up this 3,000-word disquisition, though I think she would have listened to every word with genuine care as she deftly performed her twin roles of grief counselor and vet tech.

The process of euthanasia (from the Greek for “good death”) is quick—as quick as it feels as we get to have our beloved pets in our lives before they’re gone.

Their eyes stay open, after they have passed. I looked into Hugo’s, milky white from the cataracts of age. I got down onto my haunches and gazed into them, trying to read in them a ledger of his life. I still sort of expected them to blink or move, his eyes, as when I stirred from a deep, mid-day snooze before he’d scramble up to his haunches for some scratches.

Now finally still, they were still soulful. True to a dog so sweet, loved and loving, loyal, happy, gentle, sometimes goofy, often pensive—and living up to every bit of the name Hugo.

Leave a reply to insightfulzombie47a64e0c6e Cancel reply