The name for an increasingly international movement already has some very “international” etymologies.

In the wake of the reelection of Donald Trump, there is increasing discussion of a radical feminist trend called the 4B movement.

Originating in South Korea in the mid-2010s, the 4B movement calls for straight women to “swear off men” to protest and protect themselves against violence, misogyny, and inequality.

In the movement, women refuse to 1) have sex, 2) bear children, 3) date, and 4) marry. In transliterated Korean, each of these four commitments begins with b:

- bisekseu (no sex)

- bichulsan (no childbirth)

- biyeonae (no dating)

- bihon (no marriage)

While some of its proponents are strict adherents, recent interest in it in the US more generally centers on resistance to the erosion of reproductive rights and growing misogyny online.

(If you are skeptical of the growth of online misogyny or tempted to write off instances of it as jokes, I urge you to reconsider. Over the past decade, I’ve done and still do quite a bit of research on new words, especially terms that have emerged in digital culture, including incel and alt-right corners of the so-called “manosphere.” This research has taken me to a variety of places online. The misogyny is real. It’s very dark. And it’s very consequential. Language matters.)

I was curious about these Korean “4B” words and wanted to know more about how they work. And that, of course, compelled me to learn some Korean.

Never miss a mash! Feed your inner word nerd and subscribe to get Mashed Radish fresh in your inbox.

The Korean prefix bi–

You may note that each of the Korean words that give the 4B movement its name—bisekseu, bichulsan, biyeonae, and bihon—don’t just start with the letter b. They start with bi-.

In Korean, that bi- is a prefix, meaning “no, not,” similar to un-, and it negates the noun that follows it. It’s also pronounced more like pea, not bee.

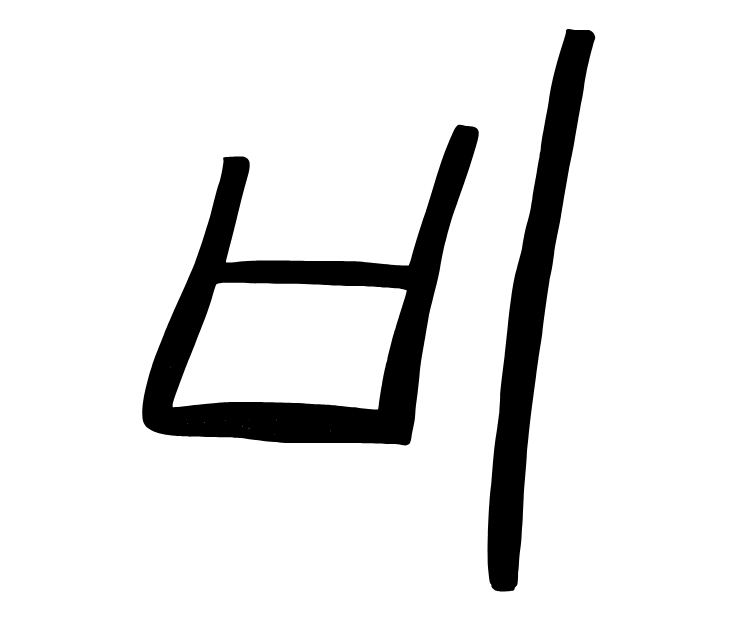

Korean uses an alphabet called Hangul, which represents 14 consonants and 10 vowels. In Hangul, the word bi– is spelled 비. The letter ㅂ is a consonant often romanized as b, although it is articulated closer to a p. The letterㅣis a vowel, rendered as i and corresponding to a long e sound, as in me.

The b’s in the 4B movement, then, aren’t just taken from initial letters. They are homophones. That’s why the 4B movement is also known as the “4 Nos.”

Some notes on Korean

An estimated 65% of Korean vocabulary comes from Chinese, a result of the extensive historical contact—and conflict—between the peoples in the regions we now call China and Korea. That loaned vocabulary, historically written in a system called Hanja, is known as Sino-Korean. We’ve already encountered one instance: bi-, itself rooted in a Chinese word for “to not be, not.”

English is brought to my mind here. An estimated 60% of its vocabulary comes from French, also through contact—and conquest. And English, of course, has immensely influenced, both colonially and culturally, languages across the world.

In addition to Korean, Chinese also massively shaped the vocabulary of Japanese and Vietnamese. While the four languages share a great deal of vocabulary in one form or another, none of them are, interestingly, part of the same language family (as such disparate and dispersed tongues as English, French, Russian, Irish, Albanian, Hindustani, and more are part of Indo-European).

The four b’s of the 4B movement

Now, let’s turn to the Korean words for what the 4B movement says “no” to.

Bisekseu, 비섹스

No sex.

Sekseu (섹스) is borrowed from the English sex.

Japanese also borrows in English in some fascinating ways. Pokémon is one compelling example.

Bichulsan,비출산

No childbirth.

Chulsan (출산) is Sino-Korean and means “childbirth, birth, labor.”

Biyeonae, 비연애

No dating or romantic relationships.

Yeonae (연애), meaning “dating, a romantic relationship, to date,” is also a Sino-Korean word based on the Chinese for “love, to love.”

Bihon, 비혼

No marriage.

The hon portion of bihon is based on gyeolhon (결혼), “marriage.” This is another Sino-Korean word ultimately from Chinese.

From 4B to 6B4T

Some feminists have extended the 4B to the 6B4T movement. As researcher Xiaoyi Cheng explains:

4B became 6B with the addition of two commitments: 비소비 (bisobi, boycotting sexist products) and 비돕비 (bidopbi, those who exercise 4 or 6B help those who exercise 4 or 6B) … the 4T in the 6B4T stands for the rejection of the modern corset, hypersexual depictions of women in the Japanese otaku culture, religion, and idol culture.

Bisobi, 비소비

“No consumption” (of sexist products).

Sobi (소비) means “consumption, spending,” a Sino-Korean word from Chinese whose characters literally mean “vanishing expense.” You’ll note that bisobi begins and ends with that same bi 비. A homonym, the latter –bi is suffix denoting “cost, expense, money.”

Bidopbi, 비돕비

Meant as “bi’s help bi’s.”

The middle syllable of bidopbi is 돕, dop-, stem of the verb “to help.”

A literal translation of bidopbi would be “no help no,” that is, the nos help the nos—those committed to the 4 Nos help fellow followers, constituting a kind of “yes,” if you will, to one another. The above-cited Xiaoyi Cheng explores how this term became translated, controversially, in China as “do not help married women.”

The four t’s

Each of the commitments in the four t’s also begins with the letter t—and tal- (탈), or an assimilated pronunciation, tar-, meaning “end of” or “out of,” akin to de-, as in deactivate.

Talkoreuset, 탈코르셋

Ending the corset.

Koreuset (코르셋) is from the English corset, used as metonymy for all harmful beauty standards.

Tarotaku, 탈오타쿠

Ending (hypersexual) otaku.

Otaku (오타쿠) is from Japanese. The word otaku—originally meaning “your home” and used as a polite pronoun in Japanese—evolved and spread in the 1980s as a term for a fanatic of anime or manga, similar to nerd or geek.

Taljonggyo, 탈종교

Ending religion.

Jonggyo (종교) is a Sino-Korean words whose characters literally mean “foundational teaching.”

Taraidol , 탈아이돌

Ending idol (culture).

The Korean aidol (아이돌) is borrowed from the English idol, here referencing Kpop girl band idols.

As awareness of the 4B movement spreads outside South Korea, it’s interesting to note how cross-cultural the Korean words for its commitments themselves are.

***

What may be most effective about the 4B movement may not be what any one of the b’s stands for—or to what extent advocates are hardcore about each of its refusals.

It’s the branding. The unfamiliarity yet memorability of its name, 4B, generates curiosity, and that is effective in bringing attention to the greater point here: respect for women on their own terms and protection of their rights over their own bodies.

Plus, it teaches us some Korean along the way.

Interested in more Korean? Revisit this explanation of the “official etymologies” of the 2018 Winter Olympics in PyeongChang, South Korea.

Leave a reply to 109: Language Oppression in Tibet (with Gerald Roche and Sasha Wilmoth) – Because Language Cancel reply