Instances of polio today are appalling—and that word is a clue to the history and origin of why polio is called “polio.”

I certainly didn’t know why polio is called “polio” until the news compelled me to find out.

Polio is a word that—for me and, I suspect, most of us—exists in history. In grayscale photographs. Photographs of iron lungs. Of young children on crutches. Of newspaper headlines announcing that Jonas Salk’s vaccine worked in 1955. (More on this below in the “Aftermash.”)

And yet polio is not just in memory—though living memory. The vaccine developed by Salk, and ones by Hilary Soprowski before and Albert Sabin after him, came during an epidemic of the disease in the United States between 1948–1955. For as much as we don’t have to think about the disease, we may well know people still in our lives who were afflicted with polio in their childhood. I do.

Polio is also now. Since 1988, a global vaccination effort to eliminate wild poliovirus has been a wild success—99% eradicated, only endemic in one type in Afghanistan and Pakistan, according to the World Health Organization.

How did the Latin word for “cow” become vaccine? Discover how.

Non-endemic cases of polio, however, have stricken people in central African countries and Indonesia in recent years—as well as Gaza, where humanitarian crises caused by the Israel-Hamas war have enabled the disease to spread in sewage. Thankfully, a humanitarian pause has successfully administered polio vaccine to nearly 200,000 children in Gaza so far.

In this post, let’s turn our etymological attention to a word, polio, many of us have the privilege not to think about. And for the history of the term, it turns out that “grayscale” is an operative word after all.

The etymology, and epidemiology, of polio

Polio is shortened from poliomyelitis, a highly infectious disease caused by poliovirus which mainly affects children under 5 and can cause permanent, sometimes lethal, paralysis.

Each part of the word poliomyelitis is taken from a Greek root:

- polios (πολιός), “gray”

- myelos (μυελός), “marrow”

- -itis (ῖτις), denoting “inflammation”

So, taken together, poliomyelitis is, literally, “inflammation of gray marrow”—that is, inflammation of the gray matter of the spinal cord.

Gray matter is a kind of nervous tissue that is indeed a brownish- or reddish-gray. The term is used especially of such tissue in the spinal cord or brain. Polioencephalitis is an analogous word for inflammation of gray matter in the brain.

The Greek myelos appears in many other words for medical conditions affecting bone marrow, such as myeloma, cancer of plasma cells. And the suffix -itis is inescapable in medicine. Arthritis, bronchitis, hepatitis, and tonsillitis are but four of countless examples.

The medical, and lexical, work of a German doctor

Now, the word poliomyelitis is a coinage credited to an influential German physician, Adolf Kussmaul. In the November 2, 1874 edition of Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift (Berlin’s “Clinical Weekly”), a Dr. Anton Fey references Poliomyelitis in the context of Kussmaul’s research on spinal paralysis. That means, in English, poliomyelitis is also a borrowing from German.

Kussmaul, who lived from 1822–1902, had an accomplished career. He was the first to describe a number of disorders, including dyslexia, though he called it Wortblindheit (“word blindness”). His name lives on in such terms as Kussmaul breathing; he noted the condition in his work on diabetes mellitus. Kussmaul even hired a professional sword swallower, the story goes, in his efforts to create a device to examine the upper part of the digestive tract.

Kussmaul is also given credit for the term Biedermeier, used to describe a period and style marked by a bourgeois aesthetic that spread in Germany and Central Europe between 1815–1848. The term comes from Gottlieb Biedermaier, the name of a fictional and parodically “basic” poet Kussmual and co-writer Ludwig Eichrodt created and featured in a Munich satirical literary magazine.

“Graying” roots

We know still more about the Greek polios (πολιός). In addition to “gray,” polios could mean “grizzled” or “grisly”—used “of wolves, of iron, of the sea,” as scholars Liddel and Scott poetically put it in their monumental Greek-English dictionary. Polios could also describe the color of hair. Poliosis, today, names a loss of color in the hair, especially in a white forelock.

Historical linguists pluck the gray hairs of polio further, relating it, via a Proto-Indo-European root *pel-, to words that variously denote loss of color: appall, pale, pallid, and pallor. This *pel– is thought to yield the Welsh llwyd, giving rise to the given names Flloyd and Lloyd. Even falcon may be a relative, if that avian’s name indeed means “gray bird,” as some suppose.

Gray. Polio. Appalling. And appalling it is to see young children—in Gaza, anywhere—have to suffer or even be at risk of suffering polio.

And yet, the reality of polio, for me and so many of us, remains a word we encounter in pictures, publications, or headlines, past and—sometimes but, hopefully, vanishingly never—present.

Aftermash

In 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt—who became paralyzed at the age of 39, diagnosed with polio—formed the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, once another term for poliomyelitis. It’s believed that Roosevelt’s polio may actually have been what’s known as Guillain-Barré syndrome.

With a since-expanded mission to fight against preventable diseases and deaths of mothers and babies, this foundation is now better known as the March of Dimes, thanks to some clever campaigning by popular entertainer Eddie Cantor. You may know him from his 1935 song, “Merrily We Roll Along,” which is the very sound of Looney Tunes.

In coining March of Dimes, Cantor was riffing on the March of Time, a newsreel series. His campaign solicited ten cents—once called a dime back in the day—in an effort to combat polio, helping to fund the research that eventually yielded Jonas Salk’s vaccine.

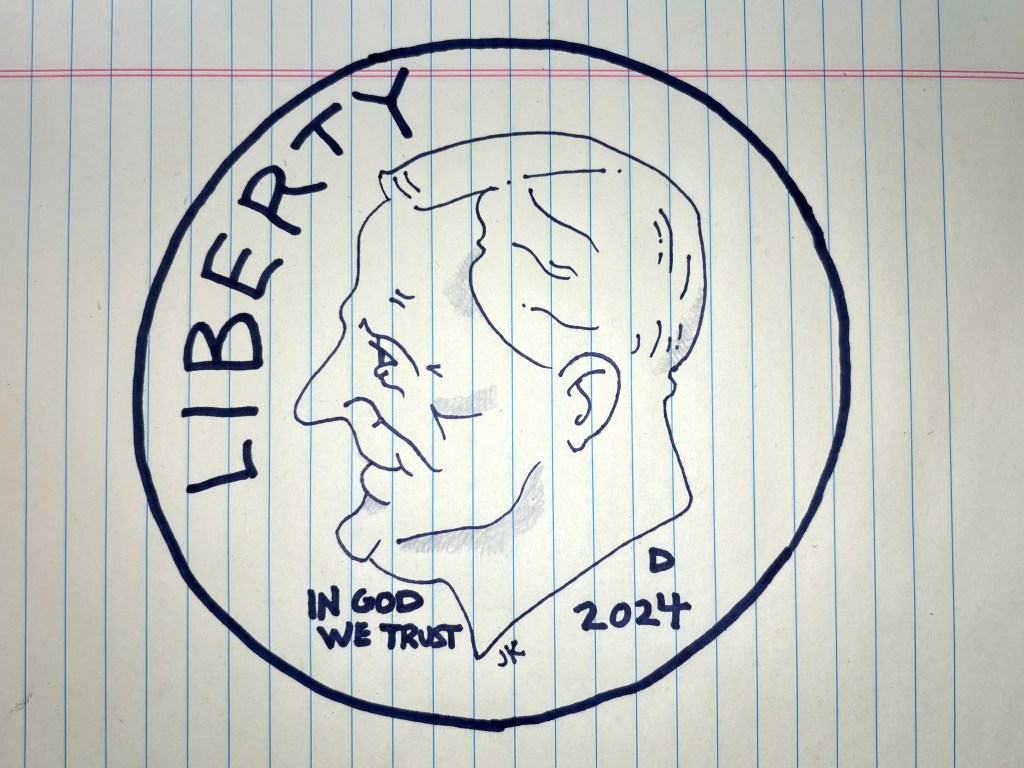

Since 1946, the US dime has featured the head of Roosevelt on “heads” (obverse) in commemoration of the president, who died in the year before—and his intimate association with the consequential work of the March of Dimes.

Leave a comment